Generated by Gemnini 3.0

Generated by Gemnini 3.0 For centuries, religion has served as a moral compass, illuminating the inner lives of individuals and offering communities a shared ethical horizon. Through faith, people have asked the most enduring human questions—about meaning, suffering, and responsibility to one another. At its best, religion has nurtured solidarity and restrained power.

But something changes when religion begins to orbit power and capital. Faith loses its sacred gravity, and institutions begin to mistake themselves for sanctuaries beyond scrutiny. Recent allegations of church–state entanglement in South Korea are not merely about one group or another. They raise a deeper and more uncomfortable question: how has society allowed religion to drift from conscience into privilege?

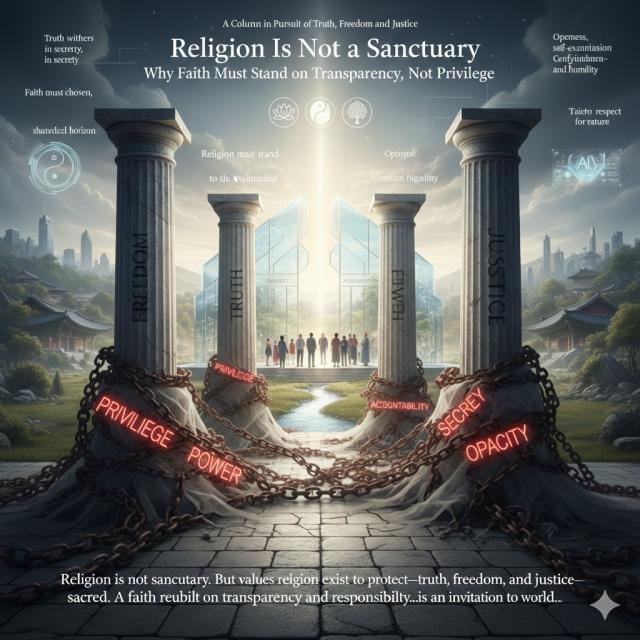

One point must be stated plainly. Religion is not a sanctuary.

Religious institutions are human institutions. They operate in society, influence politics, shape public opinion, and mobilize resources. As such, they cannot be exempt from the basic principles that govern any public actor—transparency, accountability, and equality before the law.

Freedom of religion is a constitutional right, but it exists to protect the inner freedom of belief, not to shield opaque governance, financial secrecy, or political leverage. The moment a religious organization steps into the public sphere, it must also submit to public standards. This is not hostility toward faith. It is the foundation of a democratic order.

The controversies surrounding certain religious movements—often criticized for doctrinal exclusivity, organizational opacity, and social conflict—bring this tension into sharp relief. Not every accusation is necessarily true, and vigilance against prejudice or moral panic is essential. Yet it is equally unconvincing to dismiss sustained and credible concerns as mere persecution. The answer lies neither in witch hunts nor in blind deference, but in calm fact-finding and the rule of law.

If religion is to reclaim moral authority, it must first apply to itself three basic principles.

The first is truth.

Truth withers in secrecy. Beliefs may contain mystery, but governance, finances, and public engagement must be open to scrutiny.

The second is freedom.

Faith must be chosen, not coerced. Any religion that suppresses questions or disciplines doubt has already departed from the essence of belief.

The third is justice.

Religion must stand closer to the vulnerable than to power. The moment faith begins to bargain with political authority, it forfeits its moral credibility.

These principles are not aimed at one denomination or tradition. They are questions every religious community must ask of itself. Whether church, temple, cathedral, or shrine, the path to restored trust is not complicated: openness, self-examination, and humility.

Looking ahead, this challenge becomes even more urgent. In an age of artificial intelligence—where machines increasingly replace human labor and even cognitive tasks—the role of religion may grow, not shrink. Technology delivers efficiency, but it cannot explain meaning or purpose. Here, religion could once again become a refuge for human dignity. But only if it is open rather than authoritarian, spiritual rather than institutional.

Korea, in this respect, holds a distinctive cultural asset. The ancient ideals of Hongik Ingan—to benefit humanity—and Jaesei Ihwa—to harmonize the world—express a universal ethic rooted in Korean tradition. They do not belong to any single faith. When combined with Christian love, Buddhist compassion, Confucian benevolence, and Taoist respect for nature, they suggest the possibility of a shared moral language—a Korean model of spirituality oriented toward maturity rather than expansion.

Such spirituality would measure success not by numbers, but by depth. Not by conversion, but by healing. Not by institutional size, but by the quality of human life it helps sustain.

Religion is not a sanctuary.

But the values religion exists to protect—truth, freedom, and justice—remain sacred. A faith rebuilt on transparency and responsibility, one that bridges humanity, nature, technology, and meaning, is not only a task for Korean religion. It is an invitation to the world.

*The author is the President of Global Economic and Financial Research Institute (GEFRI)

Abraham Kwak

![[포토] 폭설에 밤 늦게까지 도로 마비](https://image.ajunews.com/content/image/2025/12/05/20251205000920610800.jpg)

![[포토] 예지원, 전통과 현대가 공존한 화보 공개](https://image.ajunews.com/content/image/2025/10/09/20251009182431778689.jpg)

![[작아진 호랑이③] 9위 추락 시 KBO 최초…승리의 여신 떠난 자리, KIA를 덮친 '우승 징크스'](http://www.sportsworldi.com/content/image/2025/09/04/20250904518238.jpg)

![[포토]두산 안재석, 관중석 들썩이게 한 끝내기 2루타](https://file.sportsseoul.com/news/cms/2025/08/28/news-p.v1.20250828.1a1c4d0be7434f6b80434dced03368c0_P1.jpg)

![블랙핑크 제니, 최강매력! [포토]](https://file.sportsseoul.com/news/cms/2025/09/05/news-p.v1.20250905.ed1b2684d2d64e359332640e38dac841_P1.jpg)

![블랙핑크 제니, 매력이 넘쳐! [포토]](https://file.sportsseoul.com/news/cms/2025/09/05/news-p.v1.20250905.c5a971a36b494f9fb24aea8cccf6816f_P1.jpg)

![[포토]첫 타석부터 안타 치는 LG 문성주](https://file.sportsseoul.com/news/cms/2025/09/02/news-p.v1.20250902.8962276ed11c468c90062ee85072fa38_P1.jpg)

![[포토] 국회 예결위 참석하는 김민석 총리](https://cphoto.asiae.co.kr/listimg_link.php?idx=2&no=2025110710410898931_1762479667.jpg)

![[포토] 발표하는 김정수 삼양식품 부회장](https://image.ajunews.com/content/image/2025/11/03/20251103114206916880.jpg)

![[포토] 박지현 '아름다운 미모'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/11/19/20251119519369.jpg)

![[포토] 김고은 '단발 여신'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/09/05/20250905507236.jpg)

![[포토] 키스오브라이프 하늘 '완벽한 미모'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/09/05/20250905504457.jpg)

![[포토] 알리익스프레스, 광군제 앞두고 팝업스토어 오픈](https://cphoto.asiae.co.kr/listimg_link.php?idx=2&no=2025110714160199219_1762492560.jpg)

![[포토] '삼양1963 런칭 쇼케이스'](https://image.ajunews.com/content/image/2025/11/03/20251103114008977281.jpg)

![[포토] 박지현 '순백의 여신'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/09/05/20250905507414.jpg)

![[포토] 언론 현업단체, "시민피해구제 확대 찬성, 권력감시 약화 반대"](https://image.ajunews.com/content/image/2025/09/05/20250905123135571578.jpg)

![[포토] 김고은 '상연 생각에 눈물이 흘러'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/09/05/20250905507613.jpg)

![[포토] 아이들 소연 '매력적인 눈빛'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/09/12/20250912508492.jpg)

![[포토]끝내기 안타의 기쁨을 만끽하는 두산 안재석](https://file.sportsseoul.com/news/cms/2025/08/28/news-p.v1.20250828.0df70b9fa54d4610990f1b34c08c6a63_P1.jpg)

![[포토] 한샘, '플래그십 부산센텀' 리뉴얼 오픈](https://image.ajunews.com/content/image/2025/10/31/20251031142544910604.jpg)

![[포토]두산 안재석, 연장 승부를 끝내는 2루타](https://file.sportsseoul.com/news/cms/2025/08/28/news-p.v1.20250828.b12bc405ed464d9db2c3d324c2491a1d_P1.jpg)

![[포토] 키스오브라이프 쥴리 '단발 여신'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/09/05/20250905504358.jpg)

![[포토] 아홉 '신나는 컴백 무대'](http://www.segye.com/content/image/2025/11/04/20251104514134.jpg)